The Real Women of Petticoat Row

Note: The Research Library is open year-round, Tuesday-Friday from 10am-4pm. The address is 7 Fair Street and it is attached to the Quaker Meeting House. Learn more on the NHA’s website.

Crèvecoeur, in his 1782 Letters from an American Farmer, famously noted how the maritime economy of Nantucket engendered independence and self-reliance among the island’s women. The island’s whaling voyages often being “very long, [the whalemen’s] wives in their absence are necessarily obligated to transact business, to settle accounts, and in short, to rule and provide for their families.” This history of women’s empowerment in the family economy is well documented. Its extension into the island’s commercial economy has long been taken for granted, based largely, it seems, on the anecdotal evidence of a few well-known female merchants, such as Mary Starbuck (1645–1717) and, particularly, Kezia Coffin (1723–1798), whom Crèvecoeur describes entering the mercantile trade while her husband was making whaling cruises. Over time, the strong women of Nantucket have become embodied in the mythos of “Petticoat Row,” a street where women-owned and women-run businesses dominated the retail landscape. As an article in The Inquirer and Mirror put it in 1976, “Petticoat Row has been the nick-name of Centre Street from Main Street north towards Broad Street since the 18th Century, so called because the shop keepers were mostly ladies, usually the wives or widows of the men who were away for years at a time with the whale fishery.”

Crèvecoeur, in his 1782 Letters from an American Farmer, famously noted how the maritime economy of Nantucket engendered independence and self-reliance among the island’s women. The island’s whaling voyages often being “very long, [the whalemen’s] wives in their absence are necessarily obligated to transact business, to settle accounts, and in short, to rule and provide for their families.” This history of women’s empowerment in the family economy is well documented. Its extension into the island’s commercial economy has long been taken for granted, based largely, it seems, on the anecdotal evidence of a few well-known female merchants, such as Mary Starbuck (1645–1717) and, particularly, Kezia Coffin (1723–1798), whom Crèvecoeur describes entering the mercantile trade while her husband was making whaling cruises. Over time, the strong women of Nantucket have become embodied in the mythos of “Petticoat Row,” a street where women-owned and women-run businesses dominated the retail landscape. As an article in The Inquirer and Mirror put it in 1976, “Petticoat Row has been the nick-name of Centre Street from Main Street north towards Broad Street since the 18th Century, so called because the shop keepers were mostly ladies, usually the wives or widows of the men who were away for years at a time with the whale fishery.”

This ennobling Petticoat Row story turns out to be only partially true. The women-run retail district on Centre Street was an entirely post–Civil War institution, which developed in the 1860s and lasted into the 1930s. It comprised between two and twelve businesses at a time and involved about thirty female proprietors in all. During the island’s whaling period, which began in the 1690s and started to close in the late 1850s, women were deeply involved in Nantucket’s economy but ran just a small minority of the island’s commercial enterprises, few of them on Centre Street. Even with large numbers of island men travelling the globe by the beginning of the nineteenth century, there was no shortage of men at home. While whaling created conditions that led some island women to enter the commercial sphere, it was actually the economic and population disruptions that followed the collapse of whaling that brought Nantucket women into the paid workforce in significant numbers.

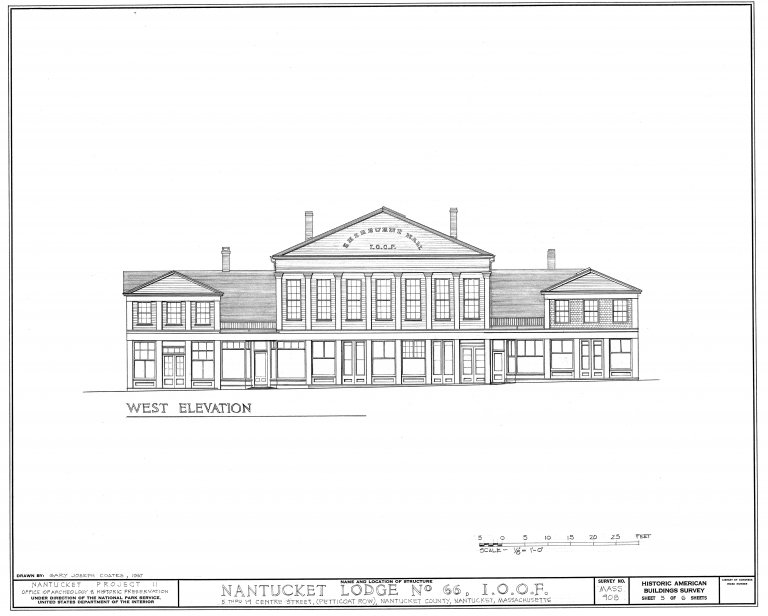

The Centre Street Block, built 1846–47. Historic American Buildings Survey drawing (HABS MA-908) by Gary Joseph Coates, 1967

The earliest printed reference to Centre Street being called Petticoat Row comes from 1903, when the Inquirer and Mirror newspaper reported on a state labor in-spector visiting “what is locally termed ‘Petticoat Row,’ where the employers are largely women.”2 No earlier print or manuscript references to the nickname have been found. A 1907 visit to the street by a reporter for the Boston Sunday Herald noted how “The fair store-keepers are not aware that they are doing anything out of the ordinary. They have been pursuing their business methods for thirty years, in a quiet unobtrusive way, and they have no idea that they belong to that new-fangled class known as ‘business women.’”

Interior of Mary H. Nye’s store on Centre Street, 1880s. Photograph by Henry S. Wyer. P3425

This reference to “30 years” is telling, for it reveals an awareness among the shopkeepers of the age of their “Row.” Far from comprising the whole of Centre Street between Main and Broad streets, the businesses visited by the reporter in 1907 were generally confined to the east side of Centre Street in the block between Main Street and Pearl (now India) Street, plus a few shops on the west side directly opposite. All the buildings here were built after the Great Fire of 1846. The heart of the block was the Greek Revival building on the east side known variously as the Centre Street Block, the Odd Fellows Building, or Sherburne Hall. This building was built in 1846–47, immediately following the fire, for whaling captains George Harris (1797–1869) and Benjamin Franklin Riddell (1804–1862). It originally con-tained six ground-floor storefronts, plus second-floor offices and a purpose-built fraternal hall for the Nan-tucket lodge of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows.

The first merchants to open stores in the Centre Street Block were all men: A. M. Macy, books; Brown & Street, boots and shoes; Heman Crocker, groceries; John P. Swain, groceries. George R. Pierce & Co. opened “the Ladies’ Exchange,” retailing dresses and fancy goods, at no. 1 Centre Street Block in 1849. Later long-term tenants included Charles H. Jaggar, apothecary (oper-ated 1856–ca. 1865) and William H. Bennett, boots and shoes (ca. 1870–89). It is likely these stores hired female clerks or assistants, but none have been identified. The owners’ wives often worked in the shops, too, as sug-gested by the experience of the Hooper family, who sold sweets from no. 4 Centre Street Block from 1850 to 1908. Linus A. Hooper (1822–1885) opened a confec-tionary there in 1850, adding ice cream the next year. He married Mary Jane Coffin (1826–1893) in 1853. After fifteen years of being advertised under his name, the store began to appear as Mrs. L. A. Hooper’s in 1865—the earliest any woman has been identified as a propri-etor in the Centre Street Block. When she died in 1893, the business passed to their son, George W. Hooper (1856–1931). He ran it with the assistance of his wife, Harriett “Nellie” Hooper (1845–1905), who is reported to have been a familiar figure at the store’s counters.

The earliest female proprietors who have been identified on Centre Street after the Great Fire are Delia M. Folger (1820–1899) and Sophia Ray (b. 1808). Delia, whose husband abandoned her for the California Gold Rush, bought a house at the northeast corner of Centre and Chestnut streets in 1859 and moved her dry-and fancy-goods store there. Sophia and her husband George ran a confectionery and stationery business (with circulating library), first from a location on Centre opposite the Congregational Church, then, from 1860, from a location at the corner of Pearl and Centre. They later moved into the Centre Street Block. Other women who opened stores between 1867 and 1869 around the intersection of Centre and Pearl include Lucy Mitchell, millinery; Eliza Ann Chase, fancy goods; Mary A. Hussey, successor to Lucy Mitchell; Mary F. Coleman, dry goods; and Sally Ann Coleman, millinery.

By 1875, twelve women ran businesses in this block, and only two male-run businesses remained. The stores specialized in women’s and children’s clothing, hats, fancy goods, notions, shoes and boots, stationery, souvenirs, confections, and ice cream. The block gener-ally maintained between eight and twelve women-run stores until about 1915, when antique and curio shops began to take over the block. As late as 1919 there were still five women-run stores on the block, and three remained in business into the late 1930s.

A number of the businesses were exceptionally long lived. Emeline Coffin was in business on Centre Street for at least twenty-six years; Phebe Clisby, twenty-nine years. The store of Charlotte Riddell, later run by her daughter, Mary H. Nye, lasted about thirty-two years. Hannah G. Sheffield took over the fancy-goods store of the late Eliza A. Chase in 1880 and retired in 1915. The storefront at 7 Centre Street was in the continuous proprietorship of women for more than eighty years, beginning about 1874, when Mary P. Swain opened a fancy-goods store there, and lasting until 1954, when Cora Stevens relocated her stationery business into a storefront on Main Street.

A majority of the female proprietors of Centre Street were single women or widows. Of thirty-two propri-etors operating between 1859 and 1940, fifteen never married or were single when they ran their stores, five opened businesses after being widowed or abandoned, and one supported an unemployed husband before being widowed. Of the ten proprietors who were married, four worked with their husbands, and two were the wives of mariners.

Centre Street grew into a nexus of women-owned stores in the 1860s and 1870s, but it was not the only street in town in which women ran stores. Roland B. Hussey, in a reminiscence of island businesses in operation in the half century between 1863 and 1913, remembered twenty-one female proprietors on Centre Street and sixteen elsewhere in town.

What of women-run businesses on Nantucket before the advent of Petticoat Row? Certainly the island had well-known enterprising women. Kezia Coffin, already mentioned, ran a substantial mercantile trading busi-ness before and during the Revolution and is reputed to have profiteered from smuggled goods during the wartime embargo. According to family memory, Anna (Folger) Coffin (1771–1844), mother to the anti-slavery and women’s rights lion Lucretia Mott, sold “East India goods” from a front room in her Fair Street house to support her family when her husband was thought lost on an 1800–02 whaling voyage. Betsey (Swain) Cary (1778–1862), widowed at thirty-four when her China trading husband, James, died at Canton, is best known for operating the Washington House hotel on Main Street from about 1816 to 1831 and later a store and public house in ’Sconset. The widow Elizabeth (Coffin) Chase (1777–1844) sustained heavy financial losses when the dry-goods and variety store adjoining her home on Winter Street was damaged by fire in January 1834.

In whaling-era Nantucket, women worked most commonly in the home or on the island’s farms. This labor was unpaid but essential to the prosperity and survival of the community. Like their sisters on the mainland, Nantucket women managed family affairs and fortunes when spouses were absent and during what one historian calls the “complex financial transactions involved in widowhood.” They were active leaders in Quakerism but were customarily excluded from elected office, the law, and most professions. Some owned shares in whaling vessels. Like other women in America, island women supplemented their household incomes by exchanging handwork or the products of their kitchens and gardens for money or goods, and many assisted without pay in their spouses’ commercial enterprises. When women participated in the paid labor market, it was generally as weavers, seamstresses, dressmakers, teachers, boarding house operators, tavern keepers, shop clerks, and shopkeepers—occupations that extended the family economy into the public sphere. Shopkeeping was an accepted and common occupation for women in Colonial and Early Republican America; more than 300 women retailers have been identified in Philadelphia and New York, for example, between 1740 and 1775. The factories that grew to employ thousands of working-class women elsewhere in New England hardly touched Nantucket, with the exception of the Atlantic Straw Works and its more than 200 female operatives, who made hats and bonnets on Main Street between 1853 and 1866.

Jedida (Swain) Lawrence (1777–1861). As a young widow, she opened a dry-goods store on Mill Street to support her seven children.

The exact number of female business proprietors on island is difficult to assess during the whaling period due to fragmentary sources, but it appears to have been quite modest. Newspaper advertisements provide a partial view into the island’s commercial landscape during the final decades of island whaling, particularly for retail businesses that needed to announce the arrival of new, perishable, or fashionable stock. A periodic survey of island newspapers between 1816 and 1845 identified ads for about 215 separate business establishments or endeavors, all owned by men except for those of these eight women: Susan Ellkins, boarding house on Main Street, 1821; Betsey Cary, boarding house on Main Street, 1825; Polly Burnell, cloth sales, 1821, and sea-shells on Ray’s Court, 1840; Mrs. Gale, apothecary, 1830; Eunice H. Elkins, millinery, 1833; Lydia A. Swain, straw bonnets on School Street, 1835; Thankful Davis, leather, 1835; Mrs. L. Butler, boarding house in Edgartown, 1835. While this source very likely underrepresents women’s businesses, it is suggestive that the proportion is so small—only 3.7 percent of the sample. Of the businesses in this sample whose locations are named, only nine were on Centre Street, all run by men.

Another source for identifying women-owned stores is an 1882 list, compiled by former Nantucket residents living in Boston, of every business they could recall predating the Great Fire of 1846. Published in The Inquirer and Mirror, the list contains some 300 businesses, thirteen (4.3 percent) with female proprietors:

Centre Street: Avis Pinkham, cake and pastry

Main Street: Eliza Riddell, dry goods; Abby Betts, variety

Mill Street: Hannah Fosdick, grocer; Mrs. Lawrence, dry goods

Pleasant Street: Mrs. Gardner, grocer

Winter Street: Elizabeth Chase, boots and shoes

Fair Street: Sarah Swain, baker; Ann Castle, dry goods

Federal Street: Lydia Hosier, dry goods; Nancy Hussey, variety; Mrs. Thompson, ice cream and confectionery; Mrs. Coffin, hotelier (Mansion House)

A third source, very late in the whaling period, is the business directory included on Henry F. Walling’s 1858 map of Cape Cod, Martha’s Vineyard, and Nantucket. It names only a doctor, a photographer, and Jaggar’s apothecary on Centre Street.

Examining the biographies of the female shopkeepers listed in these sources suggests women were most likely to open stores if widowed or unmarried. Polly (Giles) Burnell (1777–1854) lost her husband of three years at sea in 1798, leaving her alone to support their young children and, eventually, her aged mother. Sometime before 1816 she began retailing cloth, continuing until at least 1825 when her politician and banker son was well of age. From about 1831 until her death in 1854, she sold Pacific and Indian Ocean seashells, gathered by her whaling friends and relations, from her house on Ray’s Court. Her sister-in-law, Susan (Burnell) Ellkins (1781–1861), also a widow, ran a boarding house. Jedida (Swain) Lawrence (1777–1861) was pregnant with trip-lets when she lost her husband and a daughter at sea in 1809. With seven total surviving children, she eventually opened a dry-goods store on Mill Street. Lydia (Austin) Hosier (1788–1866) was also pregnant, with her fifth child, when her husband of nine years died in 1818. She, too, turned to drygoods retailing, opening a store in the ground floor of her Federal Street home. Eunice H. Elkins (1789–1872) lived off island with her merchant-captain husband, but, when he died in 1823, she returned to her native Nantucket and turned to dressmaking and millinery to feed herself and her surviving daughter. Ads for her Broad Street business disappear from the local newspapers after her 1836 marriage to William Whippey, a retired whaling cap-tain. Finally, Avis S. Pinkham (1820–1864) supported herself and her widowed mother with a cake and pastry business from their house on Centre Street, apparently stopping when the Great Fire destroyed the house. She switched to teaching and never married.

It is a myth that women took a large role in the island’s retail commerce during the whaling period because the men who might otherwise have run stores were away at sea. As island whaling became more pelagic and its voyages longer in the eighteenth century, the men who worked the island’s whaling vessels at any given time became generally a separate group from the men who worked the island’s factories, shops, stores, and countinghouses. Nantucketers, in fact, had difficulty finding enough men to man their ships, not because there were insufficient island men to fill the berths, but because whaling was terrible work. Foremast hands rarely signed on more than once or twice. Islanders consistently recruited half or more of their crews from off island between the end of the War of 1812 and the 1860s. While island mariners frequently opened shore-side businesses after retiring from the sea, there were never so many island men away whaling that shoreside jobs could only be filled by the island’s women.

For example, the U.S. Census says that in 1840, near the height of island whaling, Nantucket had 9,012 res-idents. Fifty-three percent were men and 47 percent women. The employed population was accounted to be 2,497 persons, including 1,615 “employed in navigation,” 526 in manufactures and trades, 118 in agriculture, and 11 in learned professions. The island’s 33 “retail dry goods, grocery, and other stores” employed 227 persons. Those employed equaled 27.7 percent of the total population or 52.2 percent of the male popu-lation. Looked at another way, those employed equaled 69.0 percent of the working-age male population be-tween the ages 10 to 60. Even if all men “employed in navigation”—one-third of the male population, the same seafaring percentage as Barnstable County at this time—had been away at once, there were still enough ablebodied men on island to fill the available jobs.

This changed in later decades, causing Nantucket women’s non-domestic labor participation to increase as island whaling decreased. The collapse of the whaling economy led to a steep decline in population, as single men and young families moved away in search of jobs. Women started to outnumber men, and the population skewed older. In 1830, about 3.3 percent of the island’s 7,202 residents were age 70 and above. By 1870, the population had dropped to 4,123, yet 11.9 percent were 70 and above. By 1880, the island was 56 percent women and 44 percent men, a proportion of about five women for every four men. No wonder outsiders felt that “The stores are largely owned and conducted by women.” A news item repeated in many mainland newspapers in 1881 told how three of the island’s six pulpits were filled by women one Sunday (Rev. Louise S. Baker at the Congregational Church, Rev. Phoebe A. Hanaford at the Unitarian, and Rev. R. Ellis of New Bedford at the Colored Baptist Church). “This is the normal condition of affairs in a commu-nity of women like this, where the females outnumber the males in the proportion of sixteen to one [sic]. The flagman at the railroad crossing is a woman. The restaurant at Surfside is kept by a woman—and it is need-less to say well kept—and women hold many positions normally held by men.”

When Hannah G. Sheffield died in September 1923, she was memorialized on Nantucket as the last of the old-time women merchants of Petticoat Row.10 The number of women’s stores on the Row had dropped by half in 1915 and 1916, as hats, stationery, and fancy goods gave way to antiques, curios, rugs, and jewelry. The seeds of this transformation were planted in 1884, when Jacob Abajian (1860–1937) opened a rug and curio shop in the Odd Fellows Building. His store remained in business for over fifty years, selling china, jewelry, baskets, art, furniture, clocks, and antiques targeted at the own-ers of summer homes. Prapione Abajian, Jacob’s wife, worked at the store and managed the couple’s variety business, opened at 15 Centre Street in 1912. The even-tual opening of other immigrant-owned souvenir, rug, and antiques businesses near Abajian’s Oriental Bazaar, all catering to the summer market, led The Inquirer and Mirror to complain in 1912 that “Centre Street might well be called ‘Fakirs’ Row’ nowadays . . . with its numerous oriental shops and auction rooms.”

In 1923, Helen Cartwright McCleary published a cele-bratory poem about the female merchants of Petticoat Row. It concluded,

Then here’s to Nantucket women,

In the days of auld lang syne!

Here’s to their independence

And their qualities so fine!

Here’s to the wit and humor

Of many a kindly dame!

Here’s to their industry and thrift,

Their honesty, their fame!

For sources, reference original article in the Summer 2020 issue of Historic Nantucket, read here.